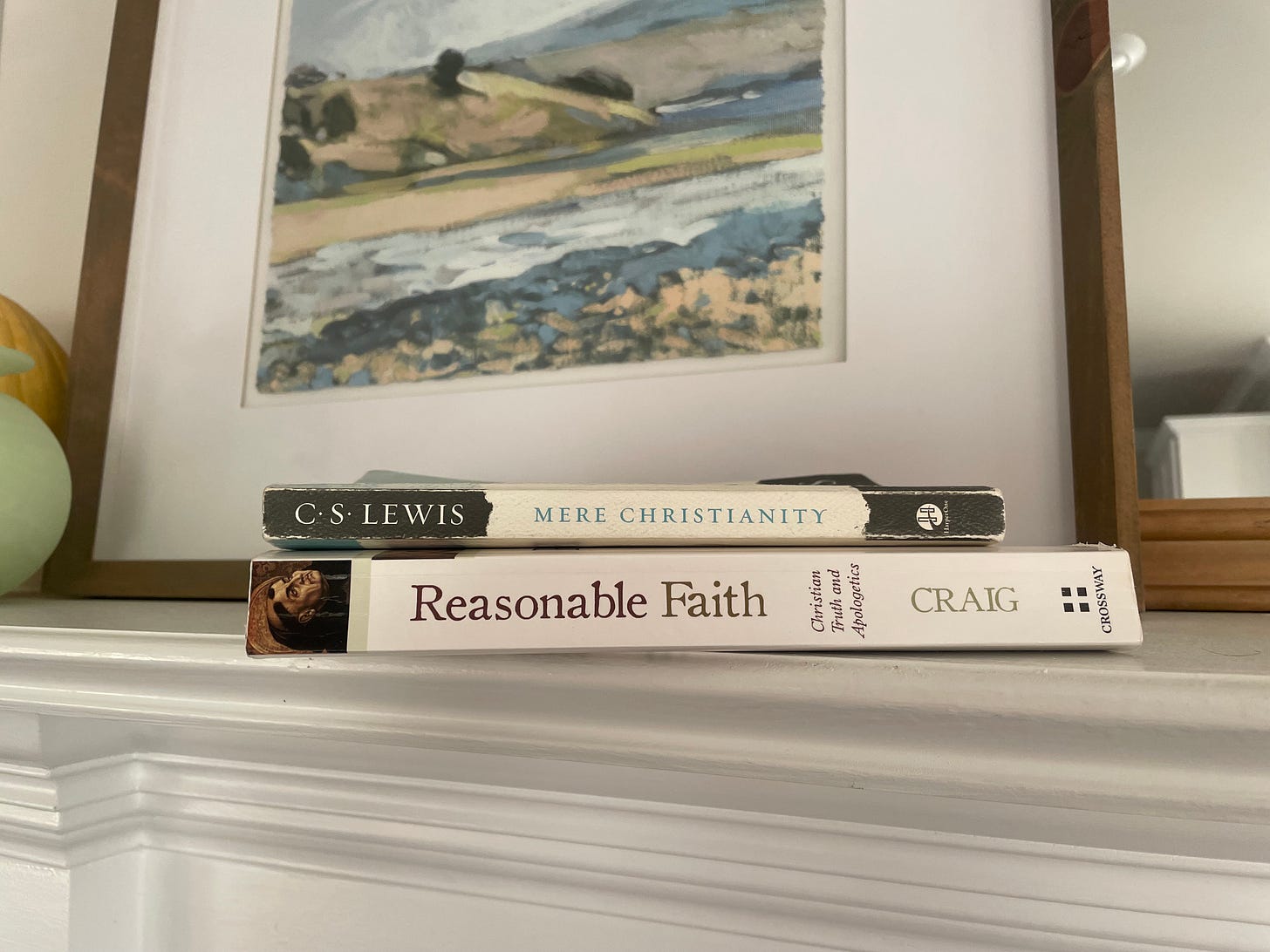

2 approaches to the moral argument

This curious idea that we ought to behave in a certain way...

Can human nature be evidence for God’s existence?

C.S. Lewis said yes.

In the opening chapter of Mere Christianity, Lewis defines “The Law of Human Nature” as the idea that, “just as all bodies are governed by the law of gravitation and organisms by biological laws, so the creature called man also had his law…but a man could choose either to obey the Law of Human Nature or to disobey it.”

Though we cannot escape natural processes like gravity or aging, we can choose whether or not to behave in the “right” way.

And, even more than that—we each seem to have an innate idea of what it even means to “behave in the right way.”

But, how do we know what “right” behavior is? Where does that sense come from?

Read on for two modern approaches to the Moral Arugument, one of my personal favorite pieces of apologetics, handled by two of my favorite Christian thinkers.

The Moral Argument in Mere Christianity

The Moral Argument is a cornerstone of Lewis’ iconic treatise on the basic facts of Christian belief. It’s not just the topic of the first chapter; it’s the idea that underlies all the other truths he describes throughout the duration of the book.

Therefore, he closes chapter 1 like this:

“These, then, are the two points I wanted to make. First, that human beings, all over the earth, have this curious idea that they ought to behave in a certain way, and cannot really get rid of it. Secondly, that they do not in fact behave in that way. They know the Law of Nature; they break it. These two facts are the foundation of all clear thinking about ourselves and the universe we live in.” (p. 8)

The big question that arises from the Law of Nature (which he also terms the Moral Law) is: how did it get there? It can’t be simply an instinct, he argues, because instincts are often simply desires, not imperatives: “Feeling a desire to help is quite different from feeling that you ought to help whether you want to or not.” (p. 9)

The very nature of this Law—the way that it binds individuals regardless of their cultural heritage, place in history, age, or status—indicates that it supersedes the simplistic evolutionary or naturalistic explanations offered for it:

“The Law of Human Nature, or of Right and Wrong, must be something above and beyond the actual facts of human behavior. In this case, besides the actual facts, you have something else—a real law which we did not invent and which we know we ought to obey.” (p. 21)

That “something,” Lewis argues, actually turns out to be a “Someone,” which we learn by examining the nature of the Law and how it acts on our rationality. The Moral Law implies a God who is, at the very least, good and powerful. Good, because he cares enough about “goodness” (or right and wrong) to imbue his creation with the Moral Law, and powerful because he has the ability to do so (in addition to creating the rest of the universe and everything in it.)

Arguing from this generically good and powerful God to the personal, triune God of Christianity takes more work—which is why I recommend checking out Mere Christianity if you haven’t had the chance to yet. But effectively, Lewis’ claim is that our innate moral sense, our desire to conform to and obey a Moral Law, is indicative of a God who sustains it all.

The Moral Argument in modern philosophy

In the time since Mere Christianity’s publication, professional philosophers have attempted to sum up the Moral Argument into a formal syllogism.

The basic claims are the same, but the language is slightly different. Where Lewis uses narrative and natural theology, traditional philosophy establishes its argument with a list of premises supported by evidence. The argument goes something like this:

If God does not exist, objective moral values and duties do not exist.

Objective moral values and duties do exist.

Therefore, God exists.

(Reasonable Faith, p. 172)

As premise 1 argues, in the absence of God (the true Good), there’s nothing (and no one) to anchor “objective moral values and duties,” or moral imperatives that apply to all people at all times. This isn’t to say that one must believe in God in order to act morally—just that there would be no such things as a moral action if there were no God.

The audience Lewis was addressing when Mere Christianity was originally published was still largely in agreement with premise 2; it was not quite yet popular to claim that there are really no objective moral values and duties that all people are bound to.

That’s not necessarily the case today. The common counterargument to premise 2 is the claim that our ideas moral values and duties are simply a product of evolutionary processes and therefore can’t be trusted. Have you spotted the fallacy in this reasoning yet? This explanation falls prey to the genetic fallacy, the claim that an argument is untrue on the basis of its origination. Whether or not our “innate moral sense” is a product of evolution has nothing to do whatsoever with the truth value of the premise itself.

Once we’ve satisfactorily defended premises 1 and 2, premise 3 naturally follows. This isn’t the most robust treatment of the argument, and there are certainly questions of Moral Platonism, warrant, and epistemology to discuss, but for our purposes those conversations will be left for later.

Paul makes it clear in Romans that the God who we worship—the God who unmistakably revealed himself through Christ and still acts via the Holy Spirit—has made his Goodness apparent to all people through a variety of means. Consider Romans 1:20: “For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made.”

A bit later, Romans 2:14-15 speaks to Gentiles having the work of the law “written on their hearts,” “by nature” doing “what the law requires” though they haven’t historically had the Torah and the prophets to follow.

Across cultures and throughout history people have sought, desired, been bound to “do the right thing.” This innate moral sense is a gift of God’s grace, a way he has revealed truths about himself to those willing to seek him.

From the archives:

Another Mere Christianity inspired post, this time tackling the all-too-modern phenomenon of “languishing” (and giving a path forward for those of us who don’t want to be sedated).