The times we live in are complicated, but we are lucky to find ourselves in a world in which Genesis 1:27 still holds some sway over the collective social imaginary.

Historian Tom Holland illustrates what I mean in his groundbreaking work Dominion. “To live in a Western country,” he says, “is to live in a society still utterly saturated by Christian concepts and assumptions.”1

For Holland, this realization occurred as he studied history, particularly the stories of ancient Rome that had fascinated him as a child.

“The more years I spent immersed in the study of classical antiquity, so the more alien I increasingly found it. The values of Leonidas…were nothing that I recognised as my own; nor were those of Caesar, who was reported to have killed a million Gauls, and enslaved a million more. It was not just the extremes of callousness that unsettled me, but the complete lack of any sense that the poor or the weak might have the slightest intrinsic value.”2

Ultimately, he concludes that the ancients seem so foreign to him because the world they lived in was based on fundamentally different values and assumptions than the world we live in today. The pre-Christian world was one in which the rich and powerful were viewed as inherently more valuable than the poor and needy; slavery and sexual abuse were accepted as standard; violent, public executions were typical fare; unwanted children were disposed of, treated as refuse.

It’s a bleak picture.

The advent of Christendom didn’t solve these problems once and for all. (If only!) Instead, it did something far more impactful: it created a world in which the central values of Christianity were known and practiced by the vast majority of individuals in the West.

The story of how culture shifted from brutal plurality to pious Christendom is too long to tell right here, right now—I’d recommend you read Dominion for the full picture. Instead, I want to dissect the idea that I see as the core of the Christian ethic: the concept that all humans are created in the image of God, with inherent worth and dignity that transcends any aspect of their identity.

“So God created man in his own image,

in the image of God he created him;

male and female he created them.”Genesis 1:27

The first temple

To understand the full significance of Genesis 1:27, it’s important to understand the narrative it’s nested within. Genesis 1 and 2 tells of God speaking the cosmos into existence, ordering primordial chaos, and ultimately creating an oasis where he will walk alongside the humans he’s created as they work to “fill the earth and subdue it.”3

But there’s deeper symbolism in this story.

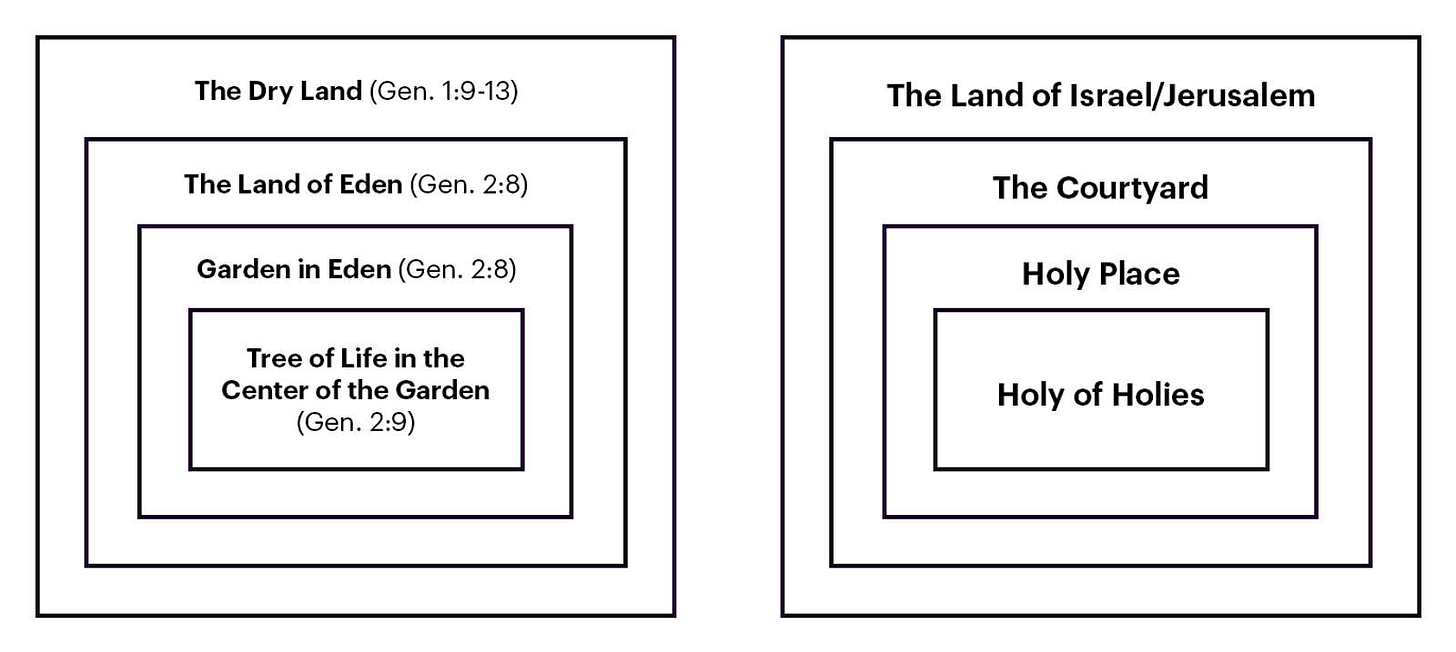

Eden isn’t just a garden, and creation isn’t just a universe: the ancient imagery of the first couple pages of the Bible reveals that it’s all a temple, a place intentionally designed for God to commune with his people.

“The concept of Eden described as a cosmic mountain-temple would not be unfamiliar to ancient readers…In the ancient Near East, the temple was the center and mainstay of creation. And in the Genesis account, the garden of Eden is depicted as the center and mainstay of God’s creation.”4

We’re meant to understand that Adam and Eve’s roles as Eden’s caretakers are effectively the roles of priests in a holy temple; their vocation is to ensure that operations run smoothly, to facilitate worship, to tame and fill and beautify the country they’ve found themselves in, and to do it all hand-in-hand with their Creator.

They’re able to fulfill that vocation because they’ve been created to do so: namely, because God has put in them some of the essential characteristics that he himself used to create the universe to begin with. Rationality, freedom of will, creativity, the ability and desire to relate to one another—all these things and more are signatures of the imago Dei, unique characteristics of God that he bestowed on humanity at creation.

Though Adam and Eve fell short of God’s design, we don’t believe that they lost that fundamental characteristic that set them apart from all other creation. The imago Dei still exists in each individual, though it may be distorted or clouded by the effects of sin.

What it means

Throughout the history of Christianity, our commitment to recognizing and remembering the inherent dignity of all people has been central to the faith’s growth and impact around the world. Paradoxically, these fundamental ideas are unnatural; in all eras, our innate tendency is to celebrate the rich, famous, and powerful, to attach ourselves to the individuals who we perceive can raise our own status, and to neglect or otherwise ignore the poor, the weak, the uncharismatic, the undesired.

Christianity teaches something different, though. Two things it tells us that the natural world can’t:

All life is precious. If Christians do not fight for the sanctity and inherent dignity of human life, who will? Forces of decreation are at work; we must be bold in our fight against evils like abortion and euthanasia, which devalue human life by reducing it to simple, sterilized metrics designed to separate the person from the body. We should never rejoice in death, we should stand up for the abused and disenfranchised, and we should be judicious in our tolerance of violence.

Everyone deserves respect. I grew up in the South, where the tradition of saying “ma’am” and “sir” is still deeply engrained. Recently, I saw someone pushing back on this trend, implying that she wouldn’t teach her children to default to calling all adults “ma’am” and “sir,” but just the ones who “earned” or “deserved” it. I recognize that, on its surface, the fact that I bristled at this concept may seem like I’m trying to hold onto some kind of stuffy, old-fashioned cultural norm that society has outgrown, but I think it’s deeper than that.

The concept that “respect is earned, not given,” is…respectfully…nonsense. We don’t defer to others because they’ve lived up to some nebulous standard, invented by us in our own heads; we do it because they are individual humans created in the image of God, reflecting some aspect of his divine nature into the world. This is true of your spouse, your family, your in-laws, your cubicle neighbor, the person you’re passing on the highway, the cashier at the grocery store down the road, your ideological rivals, and the person on the other side of the world whose path you’ll never cross.

As usual, C.S. Lewis says it best:

“It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you can talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. … There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilisations—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendours.”5

When we forget the words of Genesis 1:27, we will have forgotten the very essence of what it is to be human. The only way to preserve our world from such great tragedy is to take these words seriously; keep the teachings of this verse at the forefront of your mind by honoring others and by studying the person and character of Christ, “the image of the invisible God.”

“And one of the scribes came up and heard them disputing with one another, and seeing that he answered them well, asked him, ‘Which commandment is the most important of all?’ Jesus answered, ‘The most important is, “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one. And you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength.” The second is this: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” There is no other commandment greater than these.’”

Mark 12:28-31

From the archives:

Because sometimes you just need to hear a voice from heaven, so to speak…

A visual reminder:

Dominion, Tom Holland, p. 13

Ibid., p. 16

Genesis 1:28

The Weight of Glory, C.S. Lewis, p. 45-46